-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

Why Tsipras might gamble on snap elections

Many people asking whether Greece can afford to hold snap elections in the autumn. Perhaps, though, we should also be asking whether the country, and especially its prime minister, can afford not to.

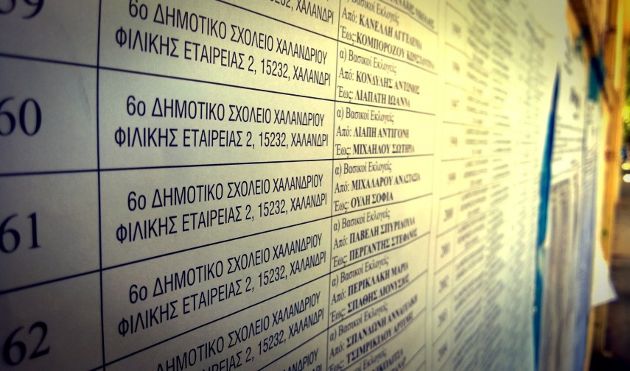

It is clear that the prospect of asking Greeks electing a government for a second time this year, between September and November, is part of Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras’s thinking, especially after seeing just 118 of his coalition’s 162 MPs back the third bailout in Friday’s vote, which took him below the absolute minimum of 120 needed in a confidence vote.

Many observers outside Greece find this idea baffling given that Tsipras has the support of three opposition parties (New Democracy, To Potami and PASOK), at least as far as bailout-related legislation is concerned. This provides Tsipras with well over 200 votes in the 300-seat Parliament and the apparent certainty of winning crucial votes in the chamber.

However, is such a marriage of convenience sustainable in the topsy-turvy world of Greek politics? It is unlikely that opposition parties will want to keep shouldering the political cost of approving unpopular measures while having no say in the way the country is being run. The situation within SYRIZA looks equally unviable as about a quarter of the party’s MPs will be voting against bailout legislation and will thus not face the same pressure as their colleagues when they return to their constituencies to speak with voters.

The only way to overcome this friction without holding new elections is for Tsipras to split with the dissenters within his party and form a new coalition government with the opposition parties. Such a move would be unprecedented in contemporary Greek politics and perhaps too big an ask of all those involved, especially when one takes into account the shift in SYRIZA policy that the last six months have prompted and that PASOK and New Democracy are essentially under caretaker leadership.

Of course, snap elections may not necessarily change much but at least it would allow the SYRIZA split to be formalised and for voters to position themselves on this fragmentation as well as whether they still trust Tsipras to run the country. There is a sense that the momentous nature of the third bailout, from the way it was agreed, the onerous content and the possibility that it will lead to debt relief, means that Tsipras needs a fresh mandate to implement it.

Without it, there is every chance that the authority of even a broad coalition will be constantly eroded by speculation about elections and the jostling between parties and MPs ahead of such a vote.

Of course, there are also much narrower political reasons for Tsipras to consider the option of snap polls this autumn. In effect, he has a small window of opportunity to capitalise on his enduring popularity before it potentially crumbles and ahead of voters feeling the full impact of the measures approved by Parliament on Friday.

In many ways, Tsipras could potentially ride a number of waves in the autumn. After clinching the third bailout with relatively minimum fuss and with positive feedback from Eeurozone decision-makers at Friday’s Eurogroup, he still has a chance to convince voters from the centre ground that he has the ability to lead Greece towards stability. At the same time, he will play up his plans for tackling corruption and social injustice in the hope of maintaining support from the left. These will be much easier messages to get across if Greeks have not yet started to count the cost of a new round of pension cuts, VAT hikes and other adjustments.

It is also worth remembering that voters have to pay several billion euros in income, property and road tax in the second half of the year. Submitting a request for a new mandate before notices for these payments start landing on the doormat may be to Tsipras’s advantage.

Striking early could also catch his rivals on the backfoot. New Democracy and PASOK have both changed leaders in the last few months and find themselves in a transition phase which, at the moment, has no clear final destination. To Potami, meanwhile, has failed to build on its entry into Parliament for the first time in January.

Tsipras’s main concern is likely to be his internal opposition. It appears that SYRIZA’s Left Platform has already begun the process of forming a new party that will advocate for Greece leaving the euro. This will be a magnet for SYRIZA’s grassroots support and the sooner elections are held, the less likely it is that the new party will be in a position to present a convincing programme that could attract more than just marginal support.

Tsipras also knows that he is currently the dominant political player domestically, with no real challengers. Somehow, he has managed to be at the forefront of developments over the last six months but also to shield himself from much of the fallout from the failure of the government’s tactics. This precarious balance will not last forever and Tsipras knows that his popularity will begin to wane in the months to come.

When this starts to happen, SYRIZA will also lose perhaps the only advantage it has over the other parties. At the moment, voters’ faith in the party is largely a vote of confidence, or at least hope, in Tsipras. Many Greeks have taken a conscious decision to cut the umbilical cord with dominant political powers of the past, New Democracy and PASOK, and to give someone new a chance. For all his faults, Tsipras currently embodies this spirit. He is not the son, nephew or cousin of a previous leader, and in Greece’s efforts to extricate itself from a crisis largely caused by chronic problems this counts for something.

Of course, it is not enough on its own and the prime minister has already shown many fallibilities and has prompted concern that he is not the agent of change he claims to be. But this means that for him there is all the more reason to obtain a new mandate before the fog of confusion lifts and voters start to pose tougher questions. This is why Tsipras could choose in the next few days to hold a vote of confidence in Parliament that he knows he might lose, paving the way for Greeks to to make a third trip to their polling stations after January's general elections and the referendum in July.

In both of those cases, Tsipras opted for a high-risk strategy, forcing snap polls in January after refusing to support the previous government's presidential candidate and then pulling out of negotiations with creditors at the last minute to ask Greeks to judge the bailout deal on offer. Both of those gambles paid off for Tsipras in a political sense as SYRIZA came to power for the first time in January, while Tsipras defeated the united force of the opposition parties, European lenders and mainstream media in the referendum. A third gamble is now on the cards and Tsipras may be feeling lucky.

*An earlier version of this article appeard in our August 7 e-newsletter, which is available to subscribers. You can follow Nick on Twitter: @NickMalkoutzis

1 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

You mean why Tsipras MUST hold snap elections?

Answer: Because ND + Pasok are at their weakest and they need to be wiped off the map.