-

Podcast - Kaisariani photos: Why Greece’s past is present

Podcast - Kaisariani photos: Why Greece’s past is present

-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

If it's debt restructuring you're looking for, Regling's not your man

The head of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) Klaus Regling leads an organisation that in its previous form as the European Financial Stability Fund (EFSF), issued loans of 17.7 billion euros to Ireland, 26 billion euros to Portugal and just under 131 billion to Greece.

In its current form the ESM has provided additional loans of 41.3 billion to Spain for its bank recapitalisation purposes, 5.8 billion to Cyprus and has committed financial resources of 86 billion for Greece’s third programme, having disbursed already 13 billion and made available another 10 billion in ESM notes in a segregated account for the latest round of recapitalisation and restructuring in the Greek banking sector.

This adds up to just under a quarter of a trillion euros in loans to five eurozone countries.

In Greece the ESM has gained a more prominent role in the negotiations and review process, having joined the other three institutions that were forming what was until recently called the troika. Specifically in the case of Greece if anyone has skin in the game, it is Klaus Regling. The ESM’s exposure, assuming it disburses the full amount it has committed and the IMF chooses to sit the third programme out – will reach 220 billion euros. Greece is expected to barely generate 180 billion euros of economic output this year.

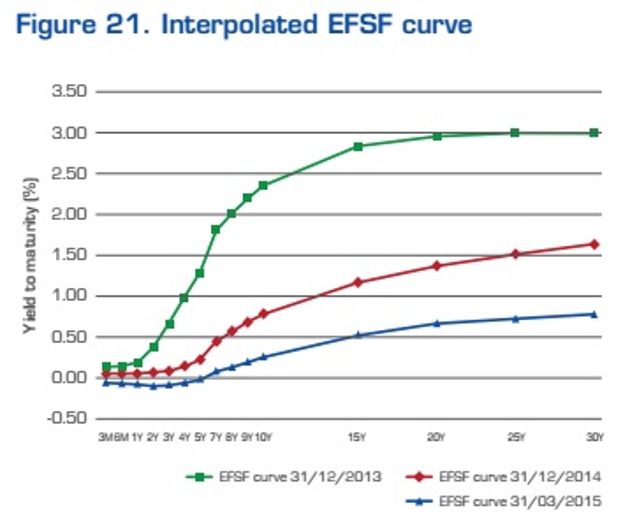

Naturally, the ESM’s managing director is often asked about Greece’s debt and its sustainability. Peter Spiegel of the Financial Times published the extensive transcript of his recent interview with Regling, in which the German official repeated his view that Greece’s debt is sustainable and does not require any extensive restructuring. His reasoning is based on Greece’s low debt servicing costs, long maturities, extensive grace periods and the newly introduced notion of gross financing needs, i.e. what percentage of the GDP is required to service and rollover debt, which according to the IMF should not exceed 15 percent of GDP per annum.

In the context of his role, his responsibilities and the nature of the ESM’s operations it is necessary that Regling’s view on Greek debt is tempered by the fact he is leading a supranational organisation that is a very active market participant. It issues debt annually in the volume of tens of billions of euros and like any other debt issuer its credibility and creditworthiness determines its market access and the cost of its borrowing.

The ESM, like its predecessor the EFSF, is simply in the business of issuing debt. The debt securities that were issued under the EFSF were backed by eurozone member states guarantees. In contrast the ESM is an intergovernmental organization with subscribed capital of 700 billion euros, actual paid in capital of 80 billion euros and a current lending capacity of 500 billion euros.

The ESM issues bonds and bills, the interest costs are pulled in and the member states that have received the loans pay the corresponding borrowing costs. Assisted by its AAA long-term credit rating thanks to its strong capital base and the backing of highly rated eurozone countries, in the event of additional capital requirements the ESM is capable of receiving very favourable lending terms and very low interest rates.

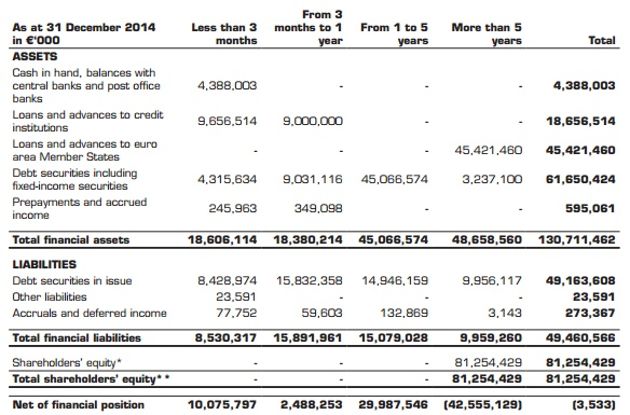

According to its 2014 Annual Report, by the end of 2014 the ESM had just over 49 billion euros of debt securities in issue. Almost half of this was in the form of bills maturing in less than one year, another almost 15 billion maturing between one and five years and just under 9 billion maturing in five years and more.

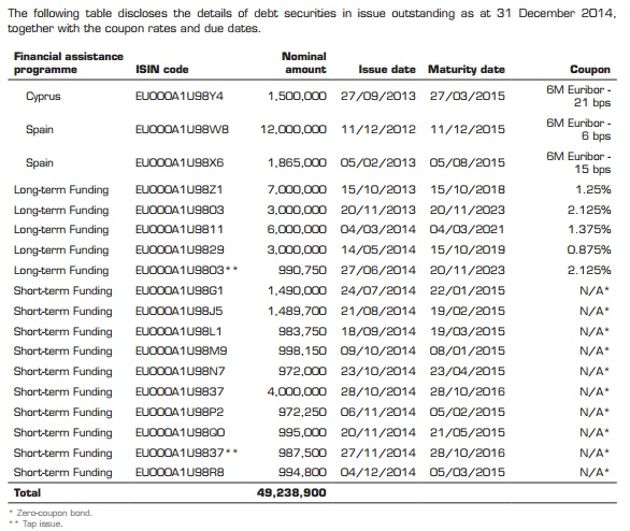

According to the funding operations section of the same report, the ESM in 2014 raised 38 billion euros in 3- and 6-month bills. In contrast, it had a target of 15 billion euros of long-term borrowing which it achieved through the issuance of bonds of different maturities.

The EFSF has a total of over 199 billion euros under its funding programme, the majority of which is now under mid- to long-term maturities and just 4 billion in short term notes although still following the philosophy of taking advantage of the low funding costs of the short end of the yield curve and lending long-term at low cost to member states. The weighted average maturity of the EFSF loans to Ireland and Portugal are circa 21 years and 32 years for Greece.

With this type of strategy in its funding operations, the ESM managing director wants undisturbed market access and it is no surprise he is not going about saying that Greece’s debt is unsustainable, which would raise the possibility of the ESM not being paid back in full.

Although the ESM enjoys a preferred creditor status, it is junior to the IMF. The private sector is left with little debt to move the needle in a debt relief exercise and the loans from the Greek Loan Facility (GLF) are a sensitive area since for most countries they constitute actual taxpayers’ money. Given the volume of its exposure to Greece, the ESM is one of the obvious areas where a debt operation would have a meaningful impact.

Naturally, the ESM head does not see the need for extensive debt relief or even debt restructuring because otherwise he would essentially be promoting the prime credit risk for his organization, as is outlined in its annual report: “the risk of loss if Member States which have benefited from the ESM’s financial stability support fail to fulfil their contractual obligations.”

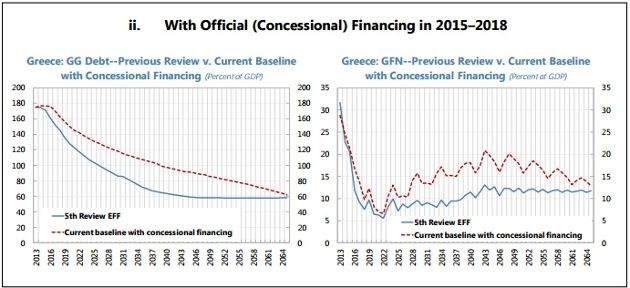

With regards to the substance of the argument that Greece does not require any significant debt operation thanks to the terms that it is currently enjoying from official sector financing, the IMF, who are the debt experts the eurozone brought into the process in 2010, presented an extensive analysis back in June. It did not even factor in the need for an additional 25 billion euros for bank support.

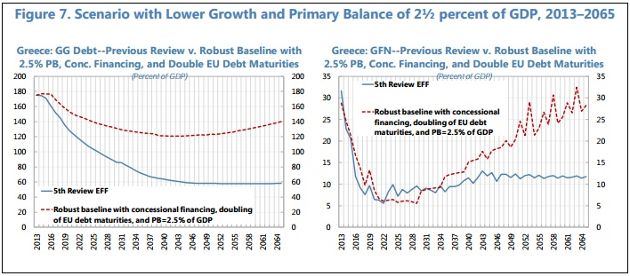

Although the IMF moved in its debt sustainability analysis from the emphasis on the stock of debt to the debt flow (i.e. how much money is required to keep the debt serviced) that is favoured by eurozone officials, the main premise remains that over the next 50 years Greece will be growing on average by 2 percent annually (which implies the best productivity growth in the eurozone) and will maintain a primary surplus of 3.5 percent for five decades. Even in this ideal world, the stock of debt would remain above 100 percent of GDP until 2040 and the gross financing needs would exceed 15 percent of GDP close to 2030, when the grace periods on eurozone loans will come to an end and Greece will have to start repaying them.

In the same analysis, the IMF presents the case of the world we live in, which is not ideal and at the same time does not include a naïve and inexperienced leftist government which wants to change Europe through tough negotiations but ends up with capital controls and closed banks. In that scenario growth projections might disappoint at times given the 50-year span of the analysis, and as a result of lower growth the primary surplus targets of 3.5 percent of GDP might become unattainable but still reach 2.5 percent of GDP, a combination that any country might face over a half a century. In that case the stock of debt will not fall below 120 percent of GDP and gross financing needs will accelerate above 15 percent of GDP after 2040.

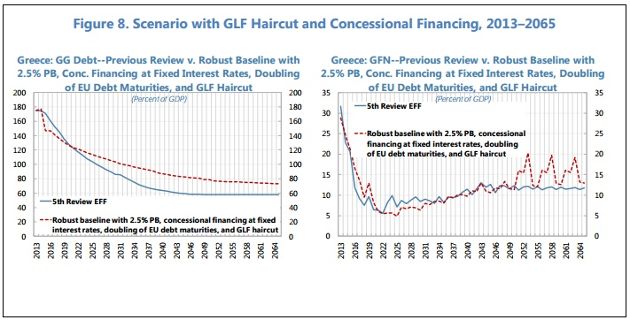

In this case, and again not factoring in the deterioration of the macroeconomic environment since the July 5 referendum was called, the IMF sees the need for a haircut in the GLF loans and interest rates to be locked in at current levels if the debt trajectory and gross financing needs are to be at safe levels over the next three decades.

Political limitations, hesitation and concerns of contagion with systemic consequences left Greece’s debt in its current state and still at the heart of the problem. Debt still shapes the agenda whether you look at it from the angle of European institutions and governments or if you want to take the view the other side of the Atlantic and the IMF.

The same limitations of the last five years will probably dictate any decisions on how to deal with it in this round of negotiations. Above all, we should not expect the ESM’s managing director to shoot himself in the foot.

*You can follow Yiannis on Twitter: @YiannisMouzakis

3 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

I tend to agree with Regling. What matters most of all is not some academic debate about what happens in 10 years+ from now. What matters is what Greece has to pay by way of debt service in the next years. And that is very, very little.

5,7 BEUR debt service in 2014. If the IMF did not charge about 3,5% on its loans and if private creditors did not cost 5-6%, debt service would be minimal. So why beat that horse to death? The discussion partner would be the IMF for an interest rate reduction and not the ESM for a haircut! And perhaps the private creditors could be paid off early.

I remember about 30-40 years ago when many where worried about what would happen to Hong Kong in 1999. And the head of Hong Kong's largest trading company said: "1999 will take care of 1999". Greece should say "2030 (or whenever the ESM loans start maturing) will take care of 2030. In the meantime, we'll try to pay as little debt service as possible and try to kick-start the economy".-

Posted by:

Foreign investors don't care about such mandate things and the rationale of cash flow bureaucrats.

When they see Greece investors focus on a 200% debt to GDP and a country lacking its own currency. This means fragility and therefore avoidance for investment purposes.

We are now in the 3rd bank recapitalization and the last thing investors want to see are their capital accounts frozen and/or raided because some clownish bureaucrat in Brussels wants to see an 11% cushion on bank capital just in case a new global crisis erupts.

Investors have zero guarantees that once they bring foreign capital to Greece they will ever be able to get it out because Greece does not control its own fate.

Greece is now a German occupied territory with decisions made in Berlin and not Athens.

Why would anyone invest in an foreign occupied country?

-

-

Posted by:

Years ago the institutions have shot in their own foot when they started supporting Greece. It is rather improbable that they will repeat it!