-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

The great turn-off: Greece's TV permits auction

At the start of the process to auction four TV licenses in Athens last week, one of the people in the room was taken to the hospital. He may have been the lucky one.

By that point what began as a supposed effort to establish some order in the opaque world of Greek broadcasting had descended into near-farce and become mired in controversy. The government’s claim that it was on a crusade to smash the so-called “triangle of corruption” between politics, media and big business was made to look like window dressing, in a tender process that left much to be desired.

The coalition had billed the first tender of its kind in Greece as a watershed moment, stressing that it was open to bids from international broadcasters and highlighting that the competition had been advertised in the Wall Street Journal. Despite the apparent intentions to turn a new leaf, this week’s proceedings had an air of more of the same.

There was no declaration of interest in the tender from outside Greek borders, apart from a Cypriot company that is reportedly linked to business interests in Greece. In fact, in its stated bid to bring a new ethos to Greek broadcasting, the SYRIZA-Independent Greeks government managed to attract a collection of existing channel owners, oligarchs, a construction magnate and football club chairmen, one of whom is under investigation for match-fixing. This motley collection of usual suspects did not seem to herald a new era for TV in Greece.

Beyond that, the start of the auction was greeted with the launching of legal action by all and sundry against the government and each other. Also one of the bidders, who attracted negative media attention over securing public contracts, produced his letter of guarantee after the deadline but was still allowed to take part. There were also reports that one of the media owners was involved in two separate bids, which does not seem to have been precluded by the rules, much to the surprise and chagrin of employees at the existing station. One of the channels taking part accused the state’s legal counsel of having recently represented one of the other bidders in court.

Finally, to add to the surreal nature of the event, army cots were set up in the building where the auction took place as the process was expected to last a couple of days (nobody had a clear idea of exactly how long it would take) and none of the representatives were allowed to exit the premises once they had entered it. Communication by mobile phone was also banned.

The tender was already under the spotlight because the government decided to limit the number of licenses to just four, meaning that some existing stations would have to close, and because the Greek constitution decrees that the independent authority, National Council for Radio and Television (ESR), is responsible for licensing issues. The government and the opposition could not agree on a new board for ESR and the coalition decided to move ahead with the process without the watchdog, prompting accusations that SYRIZA and Independent Greeks were trying to rig the tender to shut down stations that were not providing favourable coverage in return for creating close ties with the new broadcasters, who would presumably be grateful for the limited completion they would face.

It is a real shame that the process has been undermined in this way. The nebulousness surrounding Greek broadcasting had been an open wound since the first private TV stations went on air in the late 1980s. It allowed for undesirable exchanges between the political system and media owners, gradually eroding viewers’ trust along the way.

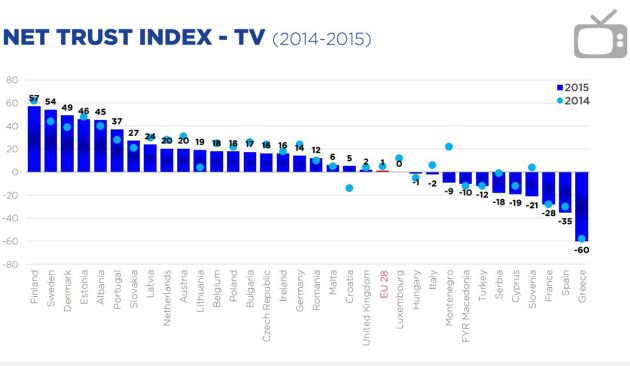

Questions about the quality and honesty of broadcasting in Greece have led to just 20 percent of Greeks trusting what they see on TV, compared to an EU average of 48 percent, according to the most recent Eurobarometer survey. In Portugal, a country of similar size to Greece, trust in TV stands at 67 percent, which is a real indictment of how badly the Greek media has performed.

To underline the level of failure, trust in TV in Greece is the lowest in the EU, according to the European Broadcasting Union. It came in at -60 last year, compared to +57 in Finland, the EU leader. Trust in radio (-24) and the written press (-33) is also very low, although not quite as poor as in TV and not the lowest in the EU. In fact, the only medium Greeks show any level of trust is in the Internet but even then it is only at +1. The greater faith in the Internet is an indication that the unreliability and hidden, or sometimes blatant, agendas of the traditional media – TV in particular – have driven viewers, listeners and readers away.

Perhaps if the TV stations had followed a different path, doing more to provide a public service, the government would have had a tougher time steamrolling its way through the tender. It may have been obliged to adopt an approach that would have allowed existing channels to pay for the right to keep broadcasting. There certainly would have been much more public demand for such a solution, compared to what looks a lot like apathy at the moment.

The failure to address these chronic failings over the years has also weakened the opposition’s voice in the debate over TV licences. New Democracy and PASOK decried the process, arguing it was unconstitutional. The conservatives went as far as saying they will change the set-up again if they come to power. However, they had more than two decades to address this issue and failed to do so. To many Greeks, the opposition’s complaints will sound like bitterness about TV channels no longer serving New Democracy and PASOK’s interests.

Perhaps, though, the biggest flaw in the process is that the criteria for qualifying as a bidder was purely financial. To be part of the auction, bidders had to provide a letter of guarantee for 8 million euros, be able to bid at least 3 million euros and commit to employing 400 people. It is true that the total of 246 million euros collected from the four bidders is an impressive amount given the starting point and the dire state of the advertising market and economy in general. But at what price has this boost for the public coffers come? What about transparency and oversight of the new broadcasters? What assurances does the Greek state have about the quality of programming and journalism? Where is the code of ethics to signal a departure from the murky past? What kind of penalties will the new channels face if they fail to meet standards? How about a “fit and proper” person rule for the owners and financial backers of the stations?

Sadly, all this was absent from the process, making the tender for TV licences a series of missed opportunities and, ultimately, one big turn-off.

*You can follow Nick on Twitter: @NickMalkoutzis

An earlier version of this article appeared in last week's e-newsletter, which is available to subscribers. More information on subscriptions is available here.