-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Are we taking Greeks' devotion to the euro for granted?

Political developments around the western world, from the victory for Brexit to Donald Trump being elected US president, have been a rude awakening for politicians, commentators and pollsters who did not see this shift in voter behaviour coming.

One could argue that the complacency of being ensconced in an environment where liberals felt they were on the right side of history and those raging against the system were deluded blinded the former to the changing political patterns. Nigel Farage and Trump have emerged as the nemesis to the hubris generated by the prevailing prosperity and stability of the last decades.

The failure to foresee the impending impact from the underlying dislocation that built up during this period has sparked much introspection. While we are at it, we might want to consider if there is something going on in Greece that we are failing to tap into.

Throughout the Greek crisis, the instability caused by the momentous economic adjustment and political foolishness never carried the full threat that it could have because there was a firm belief, backed up by opinion poll data, that the Greeks remained faithful to the euro and the European Union.

Perhaps given what has happened in other parts of the world, we need to revisit the belief that Greeks will retain an unshakeable trust in the single currency and the EU, come hell or high water. Because if we cited opinion polls as evidence of unswerving support for the European project in previous years, as further cuts were piled on and the promised recovery remained out of reach, then we should start worrying about what the same surveys are saying about the current Greek mindset on these issues.

Probably the most startling data of all is that in no other country is there as much of the population that views the EU negatively as in Greece. According to the most recent Eurobarometer survey (Spring 2016), 51 percent of Greeks have a negative opinion of the EU. That this view is shared by the majority of Greeks is a new development. There has been a 13 percentage point rise in the negative views since the last Eurobarometer poll in Autumn 2016. In contrast, 36 percent of Britons had a negative view of the Union in the poll, published in the same month as the UK referendum.

The findings mean that just 16 percent of Greeks view the EU in a positive light, well below the Union average of 34 percent and by far the lowest among the 28 member states.

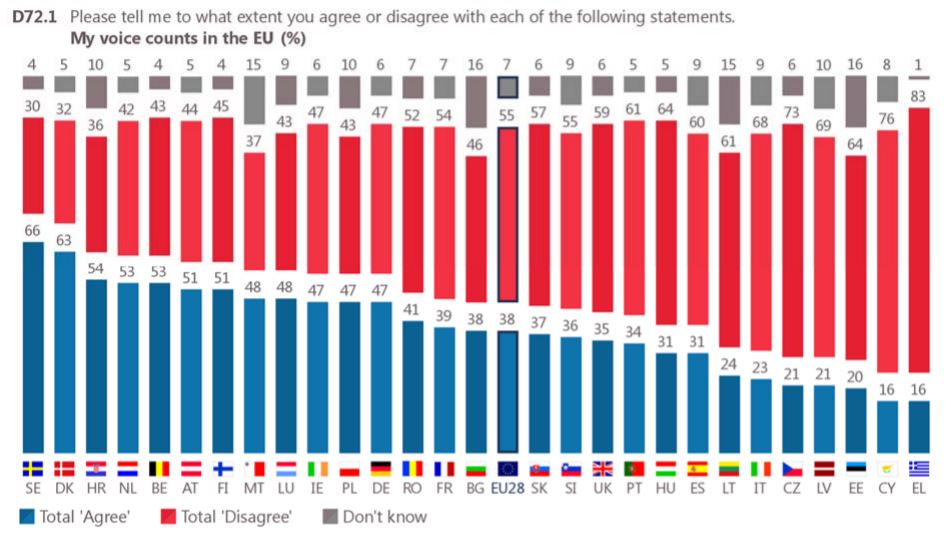

When one looks at some of the other data, it is no surprise that Greeks – once ardent Europhiles that would be found in the upper rankings of these polls – have fallen out of love with the EU. Just 16 percent of Greeks feel their voice counts within the EU. This is the lowest of all and nowhere near the average of 38 percent.

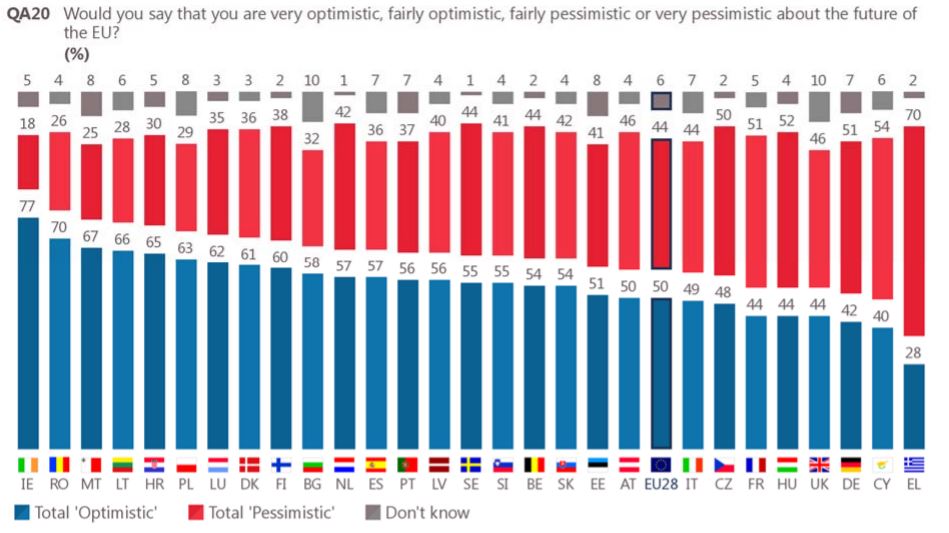

Only 28 percent of Greeks are optimistic about the EU’s future – again the lowest ranking and lagging way behind the average of 50 percent. Also, whereas two-thirds (66 percent) of Europeans feel like EU citizens, just 46 percent of Greeks feel the same way, leaving them at the bottom of the pile again.

“Ah, but support for the euro in Greece remains strong,” may be the counter-argument to this gloomy set of data on the relationships between Greeks and the EU. The statement is correct but a closer look at the figures reveals that they cannot provide much solace.

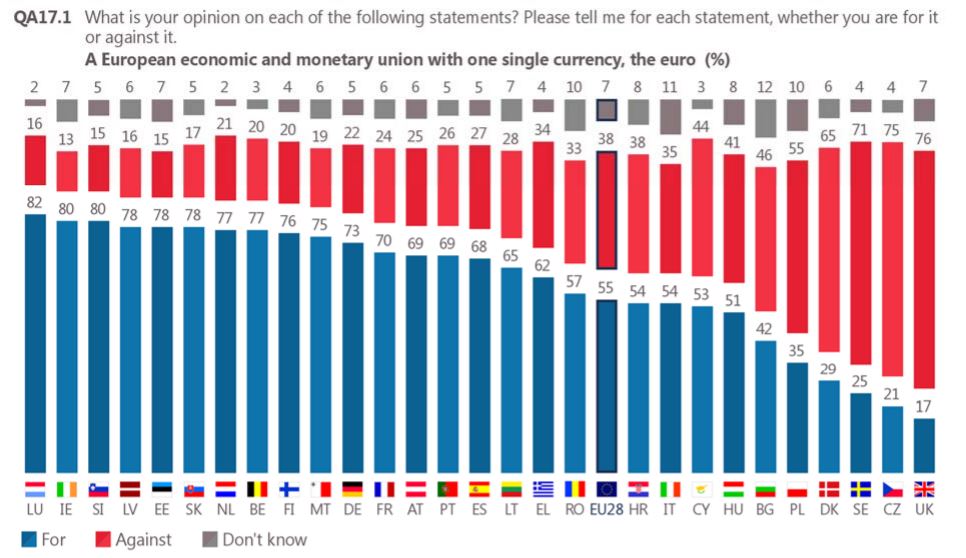

According to the spring Eurobarometer survey, 62 percent of Greeks are in favour of the euro but there are certain caveats to this. Firstly, although it is above the EU average of 55 percent, this is the fourth-lowest figure of any eurozone member. It also needs to be taken account that since this question was first asked in 2004, support for the euro has tended to average about 10-15 points higher than for the EU. Finally, Greece’s figure is eight points lower than it was last autumn (the biggest fall among all EU members during that period).

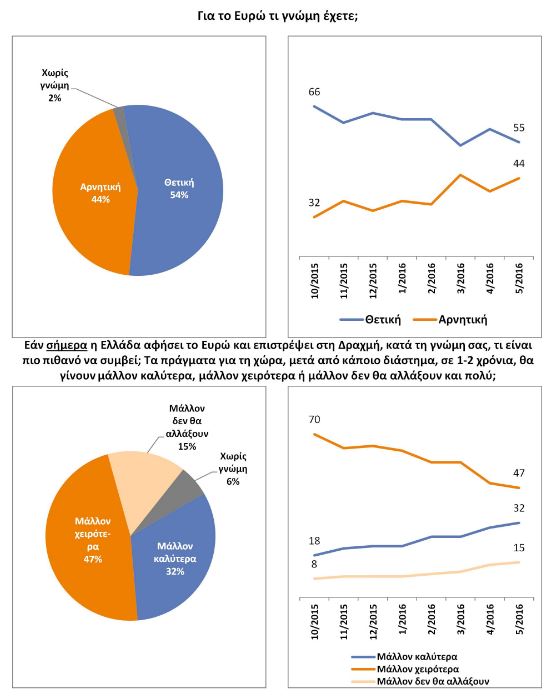

The declining support for the euro is also underscored by the findings of the most recent survey on the subject by Greek polling firm Public Issue. A poll published in May indicated that 54 percent of Greeks had a positive view of the single currency, signalling a steady decline from the 66 percent that held this opinion when they were asked in October 2015.

Public Issue also asked another question which is not covered in the Eurobarometer survey but which produces an interesting response. It asks respondents whether, in the event of Greece leaving the euro, they believe that after a period of 1-2 years the country would probably be better or worse off.

This is an interesting question because one of the issues debated vigorously last year (when the threat of Grexit peaked) was how Greece could cope with a transition to a national currency and how long the damaging impact would last. According to Public Issue, 47 percent of Greeks believe things would worsen following a Greek exit, compared to 32 percent who believe they would improve. Significantly, though, the gap between the two has been closing rapidly since October 2015, when 70 percent thought things would be worse even after 1-2 years and only 18 percent expected them to be better.

Of course, there is no imminent threat of Greece leaving the eurozone and the current government has committed itself (crucially, after staring the possibility of Grexit in the face) to keeping the country in the single currency. However, there are many challenges in the immediate future, including concluding the current review and an economic recovery materialising. Also, in the medium- to long-term, Greece will have to contend with double-digit unemployment rates regardless of whether growth meets the most optimistic forecasts.

This alone might not be enough to draw Greeks in decisive numbers to the idea of leaving the euro. The wider political environment, particularly in Europe, could also have an effect on the political options available in Greece. Should, for instance, a political entrepreneur come along and sense an opportunity in following a eurosceptic, nationalist line while the choice of exiting the euro and receiving sizeable debt relief (as promoted by German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble) is still on the table, the odds may change dramatically. We witnessed last summer how people who feel they are in a dead-end can lash out even when it doesn’t seem in their interests, when Greeks voted overwhelmingly in favour of “No” in the referendum on the bailout deal.

Perhaps our certainty that Greeks will continue to place faith in the euro is also driven by the knowledge that there is an absence of charismatic figures in the Greek political scene. We should not forget, though, that Boris Johnson and Donald Trump were able to energise campaigns instantly. Just because someone is not out there now does not mean they cannot appear in the future and make an immediate impact.

Not so many people expected Brexit or Trump to happen and they did. If we are to learn something from the way those developments caught us unaware, it is that we must not be complacent about people’s feelings and choices. The saying that men are only as faithful as their options always seemed to drip with cynicism. Perhaps, though, keeping it in mind is the best way to protect ourselves from nasty surprises.

*This article was published in last week's e-newsletter, which is available to subscribers. More information on subscriptions can be found here.

You can follow Nick on Twitter: @NickMalkoutzis