-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

-

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

-

Podcast - DETH and taxes: The only things certain in Greek politics

Podcast - DETH and taxes: The only things certain in Greek politics

-

How will Trump's tariffs affect Greece?

How will Trump's tariffs affect Greece?

An unfounded argument leaves Greece in limbo

Often, the decisions taken by the eurozone that shaped the Greek crisis at pivotal moments and sealed the country’s fate were defined by the limitations that the decision makers were facing and not the approach that would have produced the optimal result.

Greece finds itself in one of those moments again. The latest programme review has been in limbo for over a month due to an ongoing dispute between all the involved parties over Greece’s fiscal targets from 2018 onwards.

Last May, the Greek government legislated almost 3 percent of GDP in tax hikes and pension savings to meet the 2018 surplus target. It was assumed at the time that, with most of the fiscal heavy lifting out of the way, the second review would be more manageable.

The IMF believes that the measures that Greece has agreed with its eurozone lenders add up to a primary surplus of no more than 1.5 percent of GDP in 2018. The eurozone on the other hand thinks that the current agreement is enough to see Greece achieve an ambitious surplus target of 3.5 percent by the end of next year.

At the same time (and despite their different projections), there is an agreement between the institutions that Greece should not apply any more austerity.

The IMF has been vocal on this issue, with the most notable intervention coming from the head of the European department Poul Thomsen and Maurice Obstfeld, who heads the IMF’s research department. The pair published a blog post recently in which they made a comprehensive case regarding what is wrong with the current Greek programme. They asked for lower targets, a more realistic fiscal trajectory and significant debt relief. This came after the short-term debt relief measures were agreed in early December Eurogroup.

Just a couple of days after the blog post was published, Pierre Moscovici, the European Commissioner whose responsibility it is to oversee the Greek programme, wrote an article in the Financial Times in which he strongly supported Greece’s efforts so far, outlined the significant progress in the current programme and went as far as presenting data that challenged the figures used by Thomsen. Moscovici called for an end to demands that would “condemn Greece to austerity forever”.

At this juncture, the rational approach would be to stop making those demands, lower the fiscal target from 2018 and, with all parties on the same page, conclude the second review and agree the medium-term debt relief measures. However, this is where the limitations again hinder the process.

Although it is widely acknowledged that making Greece chase a primary surplus target of such magnitude will diminish the chances of economic recovery and the actual prospects of ever reaching that target, it is often argued that other eurozone member states must achieve difficult targets and, as such, Greece should not be cut any fiscal slack.

Thomsen and Obstfeld wrote in their blog: “We recognize that member states’ reluctance to accept this (and the resulting additional need for debt relief) is rooted in the reality that some of them will themselves have to run higher primary surpluses than proposed for Greece.”

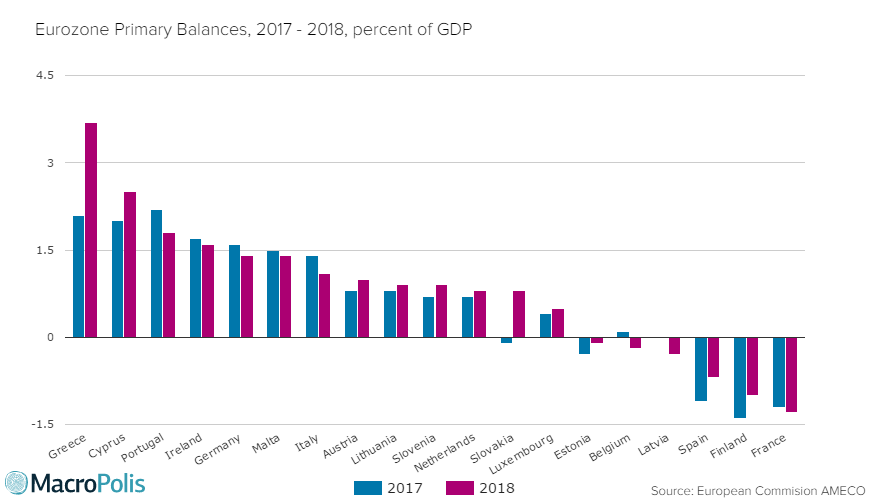

However, looking at the European Commission’s macroeconomic database that has general government statistics for 2017 and 2018, there does not seem to be any member state that has to reach a primary surplus target of 3.5 percent of GDP in 2018.

The only country that comes close to Greece is Cyprus, with a projected primary surplus of 2.5 percent of GDP in 2018. Portugal and Ireland come a distant third and fourth with 1.8 and 1.6 percent of GDP respectively.

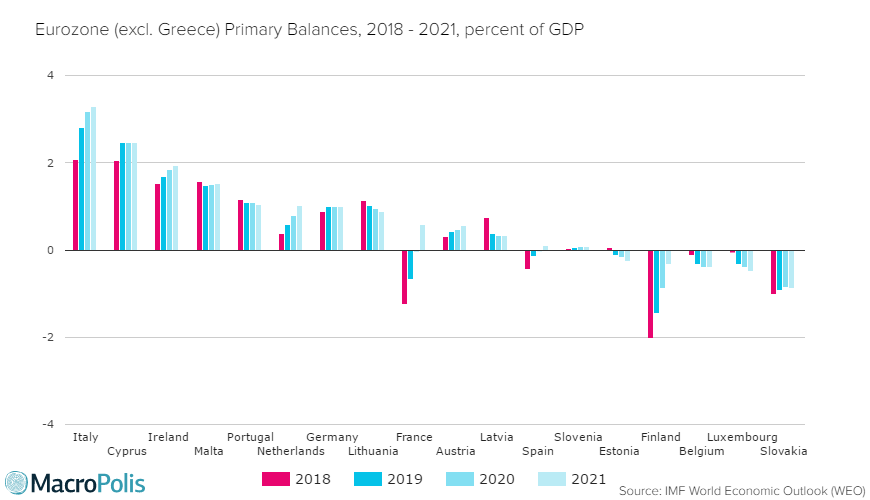

Looking further into the future using the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database, in 2021 Italy is seen with a primary surplus that exceeds 3 percent of GDP, Cyprus is expected to maintain it at around 2.5 percent of GDP and everyone else in the eurozone is below Ireland, whose primary surplus is expected to be just short of 2 percent of GDP in 2021.

Even member states that are often reported to be the most critical of Greece are not expected to run primary surpluses of more than 1 percent of GDP, while some will be running primary deficits.

It is hard to comprehend that officials so heavily involved in the Greek programme should present the existence of higher fiscal targets in other eurozone member states as reason for there being a reluctance to lower Greece’s primary surplus goal when this explanation is not backed up by the actual numbers.

Trying to reconcile differences over the fiscal issues has rapidly taken Greece from a relatively straightforward review, where labour reforms were expected to be the only truly politically sensitive issue, to German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble dropping hints about the Bundestag not approving a fourth programme if the IMF is not on board and the opposition leader in Greece irresponsibly raising the threat of Grexit in Parliament as a matter of political expediency.

One can only hope that overcoming the current impasse will not be held up by qualms about Greece requiring preferential treatment on the fiscal front given that these reservations seem to be based on a misinterpretation of reality. There have already been enough costly choices made during the Greek crisis because of decision makers being cornered by a series of limitations.

*You can follow Yiannis on Twitter: @YiannisMouzakis