-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

-

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

Of symmetry and adjustments in the eurozone

The global crisis that erupted in 2007 in the financial sector evolved into a local eurozone sovereign debt crisis in the fall of 2009, when Greece revealed serious problems in the management of public finances. Since then, the prevailing narrative has been what I called the “Berlin View”, calling into question the governments of some countries of the European periphery, particularly Greece, Spain and Italy.

Their fiscal profligacy and the postponement of the necessary structural reforms led to an overinflated public sector, and to a serious loss of competitiveness. The Berlin View, forcefully defended by the German government, but also dominant in the EU institutions, has its theoretical foundations in the neoclassical theory. In a nutshell, the theory postulates the centrality of markets populated by rational agents who, if left free to operate without distortions, tend to "optimal" equilibria, characterized by full employment of resources. Price and wage flexibility, then, ensures that demand adapts to full-employment supply.

The emphasis of the theory is therefore on supply-side measures capable of increasing the capacity of the economy to produce, and the only role of economic policy is, through structural reforms, to eliminate obstacles to the free functioning of markets. Barring exceptional circumstances, the Berlin View considers aggregate demand management useless, if not harmful. And if structural reforms, reducing wages and social protection, were to have a negative impact on the ability of households to generate demand, this would be more than compensated by the export-led growth induced by gains in competitiveness.

The Berlin View recipe to emerge from the current crisis is consistent with this framework. Countries that did their homework in the past, reforming their economy and making it competitive in international markets, may limit themselves to a temporary and conditional support to governments in trouble, that need to carry the burden of adjustment: in the peripheral countries of the eurozone, austerity and structural reforms will reduce the size of an inefficient public sector, defeat inflation, and improve competitiveness, thus helping to reduce debt (public and private) and to regain dynamism.

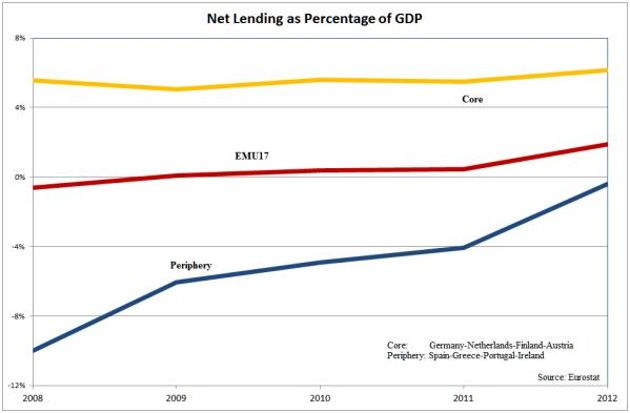

The Berlin View has dominated the political landscape: Look at the following figure, showing the evolution of net lending (a measure of change in foreign debt):

In 2008 the periphery had a deficit of around 10 percent, while the core (mostly because of Germany, of course) had a surplus of slightly more than 6 percent. Since then, the adjustment of peripheral countries has been dramatic (their net lending was virtually zero in 2012), but the core surplus actually increased, to 7 percent. It is undeniable that the adjustment, reflecting the dominance of the Berlin View, has been asymmetrical.

I would like to highlight three consequences of this asymmetric adjustment.

The first, is that the adjustment has been very painful for the countries of the periphery. Eurostat published on Friday its latest unemployment figures that, while dim for the whole Eurozone, become dramatic for peripheral countries: unemployment in October was at 26.7 percent in Spain, 12.5 percent in Italy, 15.7 in Portugal, and 27.3 in Greece (August figures). Things are even more dramatic if one looks at youth unemployment, which is close to 60 percent in Spain and Greece, and more than 40 percent in Italy. Fiscal consolidation in the periphery was not accompanied by an expansion in the core, so that the overall stance for the Eurozone was restrictive, and the slump much more pronounced than necessary.

This leads me to the second consequence of asymmetric adjustment. The increase of youth unemployment and the dramatic drop in investment rates, not only have an impact on the amplitude of the crisis in the short run. They also deepen the imbalances that created the crisis in the first place, and seriously hamper the potential for long run growth.

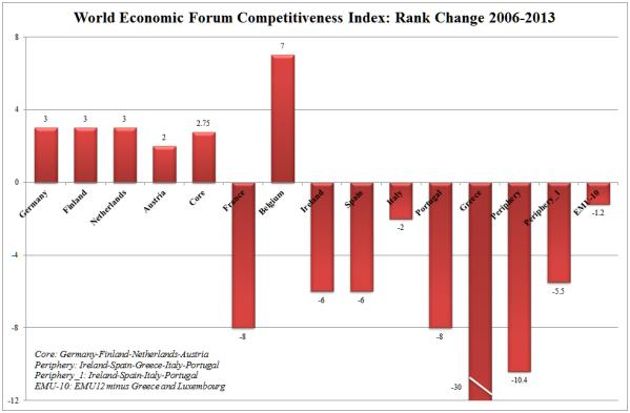

It is interesting in this respect to look at the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) published by the World Economic Forum. I am not a fan of this type of indicators, especially when making comparisons across countries. Still, they may convey some information when we observe their evolution across time. And this is what we see if we look at EMU countries:

In the figure, I report the change in ranking between 2006 (the date of the first release) and 2013. Germany for example is number four, while it ranked seventh in 2006. When averaging, I did not weigh (as I should have done) for country size. This is why I created the category Periphery_1 excluding Greece (that lost 30 positions since 2006 and biases the average for peripheral countries).

Once again I do not want to emphasize the absolute position (it means little) but the change since 2006. All the peripheral countries lost positions and became less competitive, while all the core countries improved their rankings. This allows us to assess the policies that have been followed during the crisis, and to take an educated guess on the future. The assessment is that austerity is not, as the proponents of the Berlin View would like us to believe, working to solve the periphery’s problems.

The short term pain imposed by fiscal consolidation is not planting the seeds for a future recovery based on a healed economy and improved competitiveness. Rather the contrary, actually. The divide between north and south is widening not only in terms of current growth, but also in terms of future capacity to compete and grow. This should not be surprising. As Dani Rodrik pointed out, the right time for structural reforms is during booms.

Finally, the last consequence of asymmetric adjustment is the global impact of the Eurozone crisis. Going back to figure 1, the adjustment of peripheral countries, and the continuing surpluses of the core have moved the eurozone as a whole (the red line) from a substantial balance to a small but not negligible (1.9 percent) surplus.

The eurozone today is a net saver, and therefore siphons aggregate demand from the rest of the world and contributes to depressing income at the global level. This is why today, and only today, the US Treasury (and the IMF, and the Commission) began blaming Germany’s surpluses, which existed even in the past. Add to this the fact that the ECB seems very reluctant to cooperate with the Fed to sustain the world economy, and one is left with the unpleasant feeling that the second-largest global economy is basically free riding on the rest of the world.

There are two reasons why an export-led model cannot work: The first is the many times recalled fallacy of composition: Not everybody can export at the same time.

The second, more political, is that by betting on an export-led growth model Germany and Europe will be forced to rely on somebody else’s growth to ensure their prosperity. It is now U.S. imports; it may be China’s tomorrow, and who knows who the day after tomorrow. This is of course a source of economic fragility, but also of irrelevance on the political arena, where influence goes hand in hand with economic power. By choosing the German economic model Europe would condemn itself to a secondary role.

* Francesco Saraceno is Senior Economist at OFCE-SciencesPo Paris. He holds PhDs in economics from Columbia University (NY) and the University of Rome. He served as Senior Economic Advisor of the Italian Prime Minister (1999-2002). He publishes in the fields of theoretical macro and macroeconomic policy, with an emphasis on European fiscal rules. He teaches classes on International and European Economics at SciencesPo Paris and at the Jakarta School of Public Policy, Indonesia, where he is also head of the Economics Concentration. He regularly writes columns for leading French and Italian newspapers and maintains a blog on European matters. Twitter: @fsaraceno

3 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

There is another social question.

In a macroeconomic context, a export-led growth let others countries consuming goods (and service too), and the link beetwen supply and demand stops here. The employee works to sovereign satisfaction.

A consumption-led growth, instead, establishes virtuous cycle beetwen supply and demand. So the first sustains second, and so on. The worker produces for own (future) satisfaction. -

Posted by:

@ Mr. Saraceno:

No competent economist will assume that austerity alone results in economic success.

Reading such texts strengthens my impression that countries which are too reluctant to implement all reforms required for economic success should leave the Euro instead of bashing the German approach! -

Posted by:

I don't disagree with the general tone of the article but would like to point out the following:

An export-led economy works only as long as someone else imports. For the US to (rightfully) criticize Germany for its current account surpluses is a bit of a charade. The rest of the world, particularly Germany, could not have had its surpluses if the US had not been so profligate in its external accounts during the last 2-3 decades. Yes, the consumption-addicted no-fear-of-debt-having American consumer was the locomotive behind world growth in the past. One result of this behavior can be visited in Germany's external surpluses and another one in the foreign reserves of China.

In theory, national economies should deliver the products & services which their citizens want. If they can't achieve that, they need to import products & services. To pay for them, they need to export products & services (or import capital). If the cannot generate enough funds from abroad by way of exporting products & services and/or importing capital, they need to reign in their consumption and reduce their living standard.

Over longer cycles, national living standards are a function of the national creation of economic value. No country should be forced to create economic value but no country has a god-given right to living standards.