-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

-

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

Whether an "early" or "clean" exit, it's the same old story for Greece

A two-minute video featuring Alexis Tsipras and foreign dignitaries was posted online by the Prime Minister’s Office on Tuesday. Its aim is to show that Greece is no longer in the international doghouse and has emerged as an equal partner in Europe and beyond.

The promotional video is designed to strengthen the government’s message about Greece returning to normality (a phrase used by European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker in a clip of him speaking in Greek Parliament) now that the end of the third – and final – bailout is in sight.

“Society is lifting its head and is walking steadily in a normal country,” Tsipras says at the end of the footage.

The SYRIZA-Independent Greeks (ANEL) coalition has been building towards this moment ever since it was re-elected in September 2015, this time with a mandate to implement the third MoU rather than to rip up the second, as was the case when it won the January 2015 elections.

Since the completion of the second, and most difficult, review of the current programme last June, Tsipras and his ministers have had their eyes on the prize: The conclusion of the MoU, an agreement on debt relief, a reconnection with the bond markets and the return of growth. The SYRIZA leader hopes to leave this as his (positive) legacy rather than the mayhem of the first half of 2015.

It is unlikely to be enough to prevent what currently seems like a certain win for New Democracy in the next elections but it may help restore his reputation and perhaps keep him in the political game, either if the polls fail to produce a clear parliamentary majority or in elections in the coming years.

Tsipras presents himself as being poised to stride onto virgin territory when the third MoU ends on August 20. While putting asside more than eight years of bailouts, austerity, economic depression, political turbulence and social upheaval is indeed a significant moment for Greece, the exit is not as clean as the prime minister would like.

This is not so much about whether a precautionary credit line is needed or the fact that demanding fiscal targets will remain and some form of surveillance by the lenders will continue after the summer. It is more about the idea of the exit being oversold and politics being put ahead of practicalities.

Greece has been here before. In 2014, facing the pressure of SYRIZA breathing down his neck and a public that was turning its back on him, the then Prime Minister Antonis Samaras decided that he needed a new story to present to voters. He came up with the “early” exit, announcing in September of that year that his government intended to leave the second bailout before it was due to expire.

“We need to become a normal country, and we’ve proven that we are reliable and we can stand on our own feet,” he said at a news conference while standing alongside German Chancellor Angela Merkel, using remarkably similar language to Tsipras almost four years later.

Samaras’s “early” departure from the MoU was beset by problems. The lenders were unconvinced that Greece was ready to support itself and put forward the idea of an enhanced conditions credit line (ECCL). The Greek public was also unimpressed as it had not begun to feel any positive impact from the economic recovery the prime minister heralded. Most significantly, the pledge to break out of the constraints of the programme were not accompanied by any clear commitment from the lenders on settling the Greek debt issue, while many of Greece’s structural problems, such as the public administration and judicial system, remained unaddressed.

Same again

In the roughly four years since then, very little has changed: The creditors have little faith in the Greek political system, the majority of Greeks expect their finances to worsen rather than improve, the institutions are not on the same page regarding how debt relief should work and underlying structural issues persist. And Angela Merkel is still the German chancellor.

The reason that so much is the same is that Tsipras’s focus, as in the case of his predecessor, is on the politics (how he will shape the narrative he feels will benefit him most) rather than the substance (creating the best conditions for the country going forward).

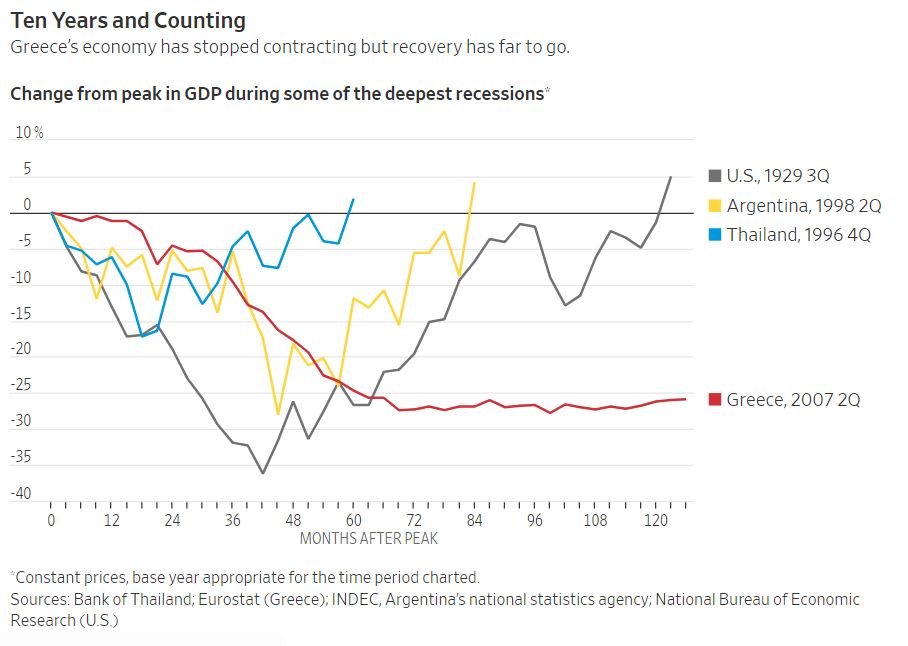

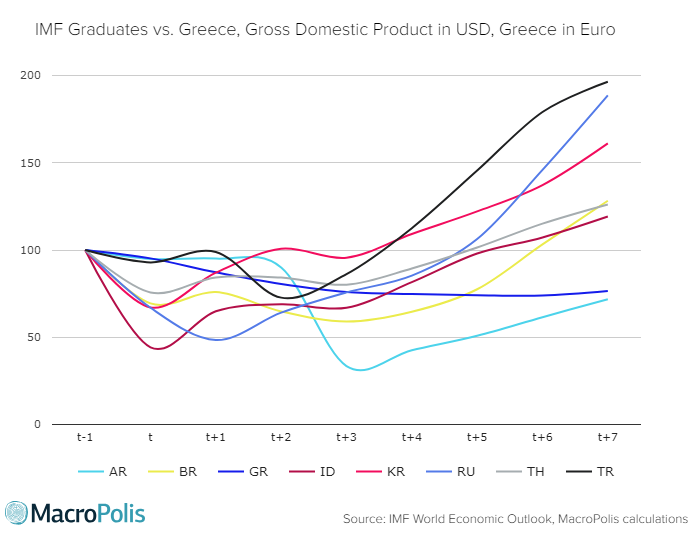

Greek leaders have stood in front of voters numerous times since 2010 and demanded sacrifices from them. Rarely have the politicians being willing to sacrifice anything themselves. This behaviour is not exclusive to Greece but other countries have not experienced its uniquely devastating set of economic circumstances over the last decade, as highlighted by the charts below (the first from this piece by Nektaria Stamouli and Marcus Walker in the Wall Street Journal).

Careers have been destroyed, businesses obliterated, families torn apart and homes lost but the political parties and their hierarchies have found a way to survive by putting their interests first when the circumstances demanded the exact opposite.

Had the reverse been true, Samaras would not have planned his great escape in 2014 but would have completed the task he took on when he became prime minister in 2012. Likewise, Tsipras would have been focused on making the right type of exit, rather than one he could claim to be clean. The emphasis on selling the idea of a decisive break from the recent past to voters has stifled any constructive debate within the government about whether a safety net was needed in the form of a precautionary credit line, even if it is just for the 12-24 months it would last, while also potentially providing access to the European Central Bank’s QE programme.The current market turbulence following the formation of a governing alliance in Italy emphasises that the Greek prime minister may be ignoring the pitfalls ahead because it does not suit the political message he wants to send.

The desperation to inflate any positives has also killed off any discussion about what specific actions need to be taken after the end of the bailout to address structural weaknesses. What has been made public so far of the government’s growth strategy seems far too vague to act as a useful guide for the country’s own reform path.

Wasted energy

It must be highlighted, though, that just as four years ago, the opposition has contributed to the current problem. In 2014, SYRIZA was promising to end austerity without explaining how it would fund its generous policies. Currently, New Democracy is seeking to tarnish any positive aspect of the imminent exit and has accused Tsipras of agreeing to a continuation of the programme.

In both cases, the opposition’s strategy has been short-sighted. SYRIZA’s vacuous approach was exposed very quickly, while New Democracy seems to ignore that if it convinces Greeks what is coming after August is essentially a fourth programme, the conservatives will be the ones having to implement it when they come to power.

SYRIZA and New Democracy have expended so much energy on trying to convince Greeks that the unattractive picture they see before their eyes is, in fact, something vastly more appealing, while also engaging in propaganda aimed at undermining each other that they are completely spent when it comes to addressing some of the issues that could change the country’s fortunes.

For instance, while Tsipras gazes into the horizon, wistfully thinking about life outside the MoU and opposition leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis beavers away furiously to prevent Greeks from believing there is anything positive to come, the creditors are – again – locked in apparent disagreement over the much-promised and absolutely vital debt relief package. It is clear the restructuring of Greece’s debt will not solve all of the country’s problems but it can, after eight years of confusion and turbulence, provide the certainty that is needed for investment and policy decisions which can aid the economic recovery.

The International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank and others are adamant that Greece’s debt restructuring after the end of the programme should be as upfront as possible and free of any conditions. Germany, and some other eurozone member states, appear to be opposed to this and want conditionality wherever possible and for decisions on additional relief to require the approval of either a European body (Eurogroup or European Stability Mechanism) or the national parliaments of member states.

Having come this far and being in such desperate need of a cast-iron commitment from its lenders so it can have a clear path over the coming years, thereby helping to restore the confidence of domestic consumers, businesses and international markets, the possibility of debt relief coming with strings attached will be a serious blow for Greece. The last eight years have shown how disruptive a policy-contingent approach can be. Greece has fiscal targets and a reform programme that it has to stick to and which can be monitored as in any other country that has exited a bailout. Adding extra layers of surveillance and conditionality to this threatens to revive the friction and resistance that so often marred the relationship between Greece and its eurozone partners since 2010. It also adds a touch of doubt regarding the future sustainability of Greek debt that may lead to higher borrowing costs for the sovereign and local businesses, acting as a brake on the recovery.

It should be the kind of development that scares the Greek political system into action. If the leaders were able to look up from their navels for a moment, they would realise that if the Berlin view prevails, a vital element of clarity about Greece’s future will disappear. They all have an interest in trying to prevent this happening.

We cannot be under the illusion that the national interest will suddenly act as a spur for Greek decision makers. But they should able to realise that any conditional form of debt relief will probably create complications for them in the future, even if they look at developments through their own, narrow political prism. They have proved masters at the later. Now would be an appropriate time to put it to good use.

*You can follow Nick on Twitter: @NickMalkoutzis