-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

From a tsunami of debt to some sense of normality

Greece’s debt managers outlined in the budget process that started last October their main goals for public debt management in the first post-bailout year.

A cautious approach was followed as Greece’s previous attempt to restore its relationship with international markets in February 2018, with a 7-year issue did, not have the desired outcome. Uncertainty, mostly caused by the confrontation between the European Union and Italy over the latter’s budget, led to Greek yields rising after the new issue, with the cost of borrowing putting on hold any further forays.

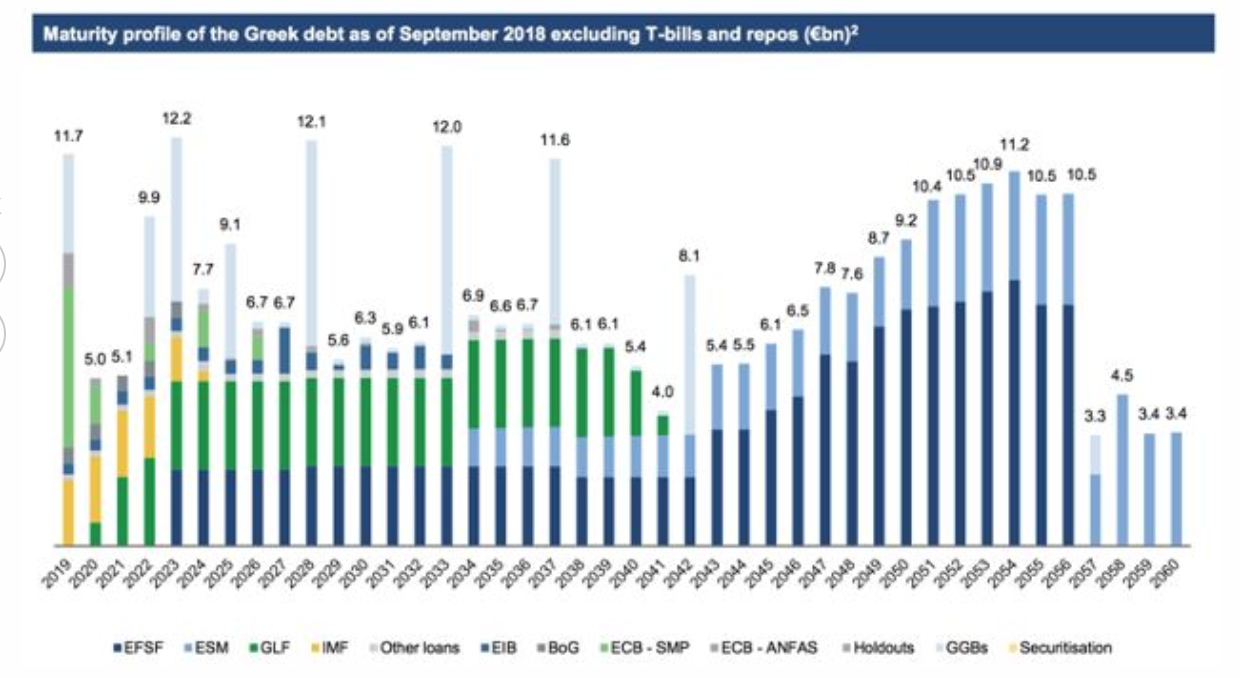

For 2019, the Public Debt Management Agency (PDMA) had a provisional goal of issuing a total of just 7 billion euros of new debt. This was due to the fact that the Greek state had built up a sizeable cash buffer of more than 25 billion euros following its exit from the third bailout in August 2018. This meant Greece was fully funded for up to two years and had a rather benign maturities schedule in the near term, following the latest round of debt relief measures agreed with the eurozone creditors.

Greece does not have to repay any programme loans before 2020, when circa 700 million of bilateral loans from the first programme are due. From the official creditors, only the International Monetary Fund is expecteding repayments of roughly 2 billion over the next three years.

Greek government bonds after the PSI, and the debt exchange of those bonds in November 2017, which regrouped and pushed further their maturities, do not pose an immediate concern. The exception is those held by the Eurosystem as part of the SMP programme and ANFA holdings.

Bond maturities in 2019 stand at just 8.8 billion euros, which takes the total of maturing debt obligations, excluding the T-bills that are rolled over on maturity, at just 11.7 billion euros, which is just 3 percent of total outstanding debt and only 6 percent of GDP.

Halfway through the year, the PDMA has achieved its goal. It has issued three bonds of 5-, 7- and 10-years for a total of 7.5 billion euros, achieving highly competitive terms, with the latest issue last week falling to a yield 1.9 percent. It was also heavily oversubscribed. This is the first time that Greece has managed to issue three bonds in a year since 2010.

One just needs to look at the debt situation Greece was facing nine years ago to realise how three programmes and incremental debt relief interventions from its eurozone creditors have transformed Greece’s debt and the solvency outlook. An IMF chart from the early programme documents in 2010 is striking.

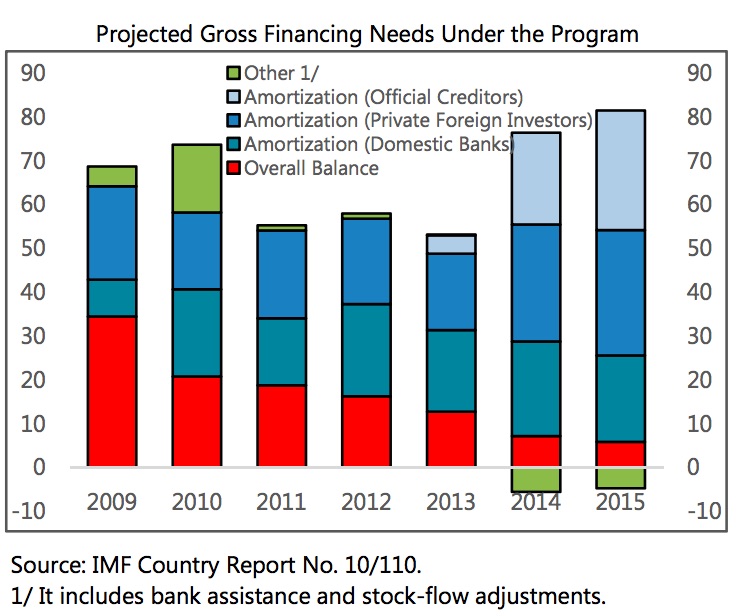

Following the disastrous fiscal policy adopted by the New Democracy government in 2009, Greece had a total deficit of 35 billion euros, combining primary deficit and interest payments.

In 2010, between domestic and foreign investors 40 billion euros of debt was maturing and would need to be refinanced.

Greece would need to find from the international investment community 75 billion euros to keep the state running, meet interest payments and stay solvent by repaying debt obligations.

The level of mismanagement and the lack of prudent planning was so striking that even following the projections of severe belt-tightening during the first programme, between 2010 and 2013 Greece would have needed more than 50 billion euros each year to stay solvent.

All this would have to be achieved in the wake of the Karamanlis administration being caught understating the fiscal disaster during 2009, when it had communicated to Brussels in September of that year that the deficit would reach 6 percent of GDP. In fact, it was at 8 percent already in August.

In 2009, Greece was facing a tsunami of debt obligations over the coming years and the misreporting by its government undermined its credibility globally.

This should have made it clear from the start why Greece went bankrupt a decade ago. But Greeks were fed numerous conspiracy theories to deflect responsibility from the Karamanlis administration and to help boost others’ political careers. Antonis Samaras and Alexis Tsipras later became Greek prime ministers after they both advocated seemingly pain-free solutions to Greece’s problems.

Greece has paid a heavy price for its antics in 2009, the populists that followed and the early decisions of key eurozone politicians, which were dictated by their own domestic political considerations. After a long and painful period, the developments regarding Greek debt show that some signs of normality are emerging.

1 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

I would like to point out that the current 'normality' of Greece's debt situation is something which could have been achieved back in 2010. All that would have been required was that creditors would have agreed to move out maturities way into the future and to lower interest rates. Actually, the PSI could have been avoided that way. In other words, the objective would have been to achieve today's 'normal' debt/interest profile at the outset so that energies would not have to be wasted negotiating the legacy over and over again.

Creditors normally don't do that right away because they want to have a trigger to be used in case the borrower does not perform. That trigger would have been there in any event because post-2010 Greece continued to need Fresh Money (for primary deficits and interest, for bank recaps, etc.) and the 'threat' of not providing Fresh Money in case on non-performance would have been sufficient.

A debt problem, even if it is as huge as Greece's was back in 2010, can be solved by a group of people in a conference room in a reasonably short time (provided that they are willing and intent so solve it). To reform the Greek economy and to get it up to speed is a project for a generation. Here was a misapplication of resources: most of the effort was spent for years on matters which could have been resolved by a group of people in a conference room and very little effort was spent on measures to get the Greek economy up to speed.