-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Tracking Greece's fiscal performance

The Covid-19 pandemic is slowly fading into the background, with the energy disruption from Russia’s invasion in Ukraine taking its place as the most acute challenge for economic and fiscal policy. In this final blog for 2022, we want to take stock of where the budgetary situation stands, and what we can say about underlying trends. Anticipating the results, we will show that the headline fiscal balance is recovering well from the large Covid-19 shock, despite the current energy price crisis.

Nevertheless, interpreting the outcome and where fiscal policy is heading in 2023 and beyond is complicated by the emergence of high inflation, and by large interest rate subsidies that Greece is receiving on its debt. High inflation helps the government to recover from the big deficits during the Covid-19 episode, but, hopefully, it will not continue for too long. The interest rate subsidies will take longer to fade away. It is important for the public to be aware that these exist and what consequences they entail.

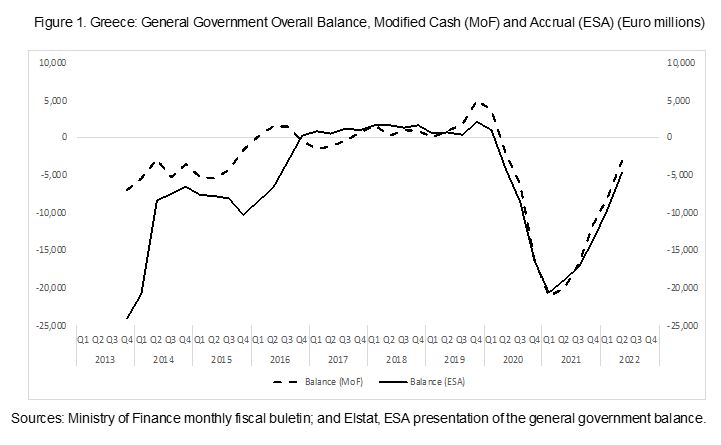

Cash vs Accrual. Let us look at what has happened with the fiscal deficit over time. Figure 1 shows the overall fiscal balance over 10 years through 2022-Q2 as reported by two key data sources: the Hellenic Ministry of Finance (MoF) and Elstat, the Greek statistical agency. Each data point represents the general government fiscal balance over the past 4 quarters. Thus, we see a moving annual result.

The data presented in the monthly bulletin of the Ministry of Finance are calculated on what is called a “modified cash basis,” the dashed line in Figure 1. This means that the original data are mostly cash outlays and expenditures in the budget, with some adjustments for commitments previously made but not yet paid for. However, quite a few fiscal operations may have an economic impact today (when they are announced or become effective) even though the government only has to pay for them later, or only receives revenues from them later (say, the revenues for the month December (commitment) are generally received in Q1 of next year (cash)). This gap between when a fiscal operation becomes effective and when the costs or revenues show up in the budget can cause a distortion in interpreting the fiscal balance results.

When the European Union developed its European System of Accounts (ESA) for fiscal policy tracking, it preferred to record fiscal developments at the time when these have an economic impact (solid line in Figure 1), even if the budget cash impact comes later. This ESA concept is called the accrual basis, or commitment basis. Elstat calculates the ESA results for the general government, which takes more time than recording the ongoing cash results, and then submits these data to Eurostat and to the European Commission, where all EU countries are assessed on the same ESA basis (the Maastricht fiscal agreements also follow the ESA basis).

In the past, Greece tended to have big differences in the Bulletin cash reporting from the MoF and in the ESA accounts for the fiscal balance, especially when the crisis broke out in 2009-2010 and up to around 2016. The deficits reported by the MoF would typically be much smaller than the deficits that would later be found when correctly applying the ESA methodology. Thus, the Ministry of Finance at times even did not know what the ESA deficit was until much later. This is a problem when deficit and debt control is a priority in fiscal policy.

Good work has been done, and, with help of technical assistance from the EU and the IMF during the adjustment programs, fiscal tracking in the monthly bulletin has much improved. This is a genuine achievement perhaps not always perceived by the broader public. Since end 2016, the modified cash basis of the bulletin and the ESA accrual accounts track quite well. The bulletin numbers now give a preview of what the important ESA numbers will show.

Almost back to balance. Figure 1 shows clearly that the fiscal balance was hit severely during the Covid-19 episode. Since Greece still has very high debt, we have advocated that the government runs a balanced budget for a while, together with structural reforms to boost productivity. We see this combination of policies as the best way forward to deal with growth and competitiveness, while gradually lowering the stock of debt in relation to GDP.

The second Syriza government set the tone as of 2016, running as disciplined a balanced budget policy as we have seen. As discussed in Blogs 10 and 11, they achieved this by raising and effectively collecting indirect taxes and limiting subsidies (good fiscal measures given Greece’s poor saving performance (Blog 23) and sky-high consumption spending relative to GDP). This was followed in 2019 by tax cuts from the incoming New Democracy government, and then with high subsidies as Covid struck, and again high subsidies in response to the energy crisis.

With tax cuts and booming subsidies, how, then, you may ask, has the deficit recovered so well from the Covid-19 dip centered around 2020-early 2021? We see three contributing reasons:

- Tax administration and expenditure control both have improved over time, again with much technical assistance and domestic hard work during the crisis programs in 2010-2018. The current government has continued these good efforts.

- Growth has rebounded significantly from the Covid-19 crisis and real GDP has now surpassed the level just before the pandemic hit. This recovery has boosted taxes and lowered the need for assistance spending.

- And Greece, like other countries in the EU, benefits in the fiscal balance from higher inflation. Inflation is a tax, because it inflates real tax revenues and deflates real expenditures. The private sector pays more and gets less, to the government’s benefit.

But, inflation is a harsh tax with many distortive effects, and it hits people in the lower and middle income brackets more than the rich, so it is also a dubious tax from the point of view of a sound distribution of income, wealth, and purchasing power. Since the structural tax base was cut by government policy, and the inflation tax has emerged in its place, we would conclude that the quality of the current fiscal adjustment is not as high as the recovery to a balanced budget in 2016. Indeed, inflation needs to come down, and when that happens, it remains to be seen if the overall fiscal balance (and the drop in debt relative to GDP) will persevere.

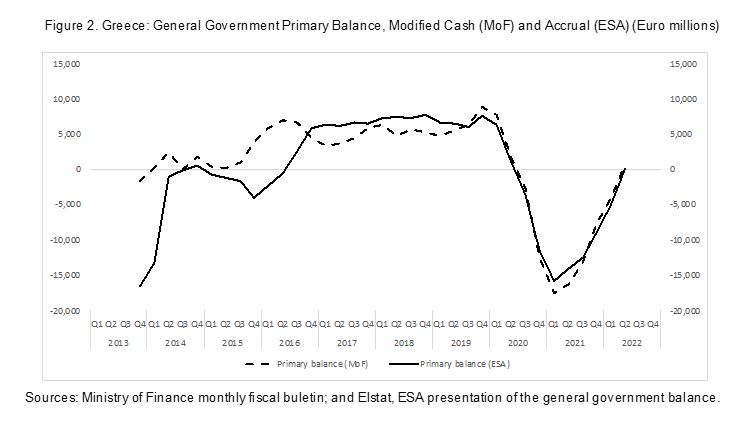

The primary balance. Figure 2 shows the general government primary fiscal balance, excluding interest payments from the overall balance above. Further adjustment between €5-10 billion (2½-5 percent of GDP) is necessary to restore a sound primary and overall balance. This is not an easy task, as the current result reflects an artificial boost from the inflation tax, which, hopefully, will soon disappear. In short, Greece is showing good fiscal progress, but more work is needed to restore more robust, sustainable, and high-quality fiscal results.

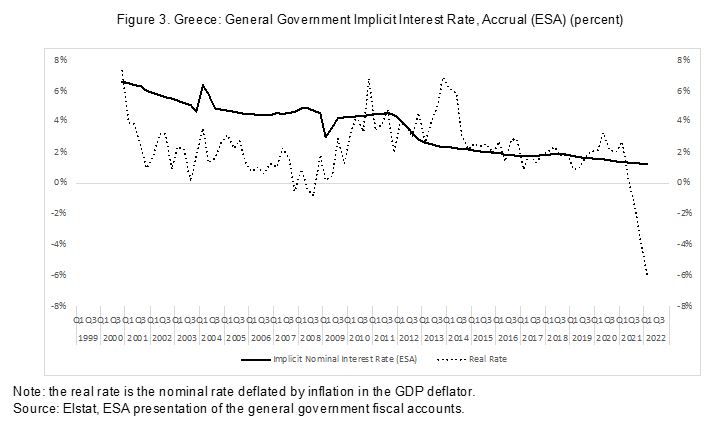

The interest bill. Finally, we can take a look at the general government interest bill (the difference between the overall and primary balances) and, in particular, the implicit nominal and real interest rates on the debt. Figure 3 summarizes the headline findings, using the ESA accrual accounts compiled by Elstat.

The solid line represents the implicit nominal interest rates on the general government debt. These were calculated as the interest bill from above (overall minus primary balance), divided by the average stock of general government debt (Maastricht definition) at the end of this year and the previous year. The dotted line deflates the nominal interest rates by inflation as presented by the implicit GDP deflator. The calculations reflect the period beginning just prior to Greece’s general use of the euro in February 2002, until 2022-Q2.

The average implicit nominal interest on the debt has fallen over time from 6.6 percent in 2000 to 1.3 percent in 2022-Q2. The drop in nominal interest rates on the debt accelerated significantly during 2011-2012 when the adjustment programs with Greece refinanced most of Greece’s bonded debt at market interest rates (and there was a nominal debt cut), with loans from the EU partner countries that carried a highly subsidized (i.e. reduced) fixed interest rate.

We can also see that as Greece adopted the euro, its real interest rates on government borrowing dropped precipitously through 2008. This sharp drop in real borrowing costs was one of the reasons for the high growth rates for Greece overall in the first decade of the euro. Real interest rates were reset to much higher levels into the emergency of the Greek crisis in 2009-2010, both because the market jacked up Greece’s borrowing costs, and because inflation came down as a result of the fiscal adjustment programs that were adopted as a condition for substantial government debt refinancing with EU partner countries.

Then, with the gradual normalization of economic conditions in Greece and a resumption of growth, real interest rates drifted down again, closely following nominal rates (Greek inflation was close to nil during this period), until the sharp boost in inflation caused real rates to plummet to -6 percent on average in 2021-2022. Since so much of Greek debt has been refinanced through EU partner countries at low fixed rates, Greece is receiving a huge subsidy on its interest bill, relative to what it would have to pay if the debt were held by the market.

We now have found two effects that lead us to recommend continued caution with the public finances for some time to come. One, inflation is contributing to making the fiscal deficit shrink. This benefit will pass as the ECB makes further efforts to bring inflation down to around 2 percent a year. And, two, with a longer-term effect, the subsidies from EU countries (really: EU partner tax payers) to lower Greek interest costs on the debt will also gradually diminish. The current interest rates perceived by Greece on government borrowing are not market rates.

But, Greece will want to get back gradually to market-based financing to reclaim full sovereignty in its economic policy making. As an example, if the nominal interest rates were to reset to the average over the first two decades of the euro (combining gradually lower debt ratios and improved credibility after the crisis), then the nominal rate would amount to some 3½ percent, instead of the current 1.3 percent.[1] This would mean that, in today’s equivalent, the interest bill would increase to 2.7 times what it is now (3.5/1.3=2.7). The current interest bill of around 2.6 percent of GDP would then be the (market) equivalent of around 7 percent of GDP.

In turn, this mathematical result is indicative of the size of the interest subsidy that Greece is receiving every year as long as the debt is held by EU partner countries at highly subsidized rates over the next decades. It is also indicative of the need for further primary balance efforts to strengthen domestic debt reduction efforts and keep the overall balance around zero, until the debt stock is brought down much closer to the 60 percent Maastricht limit agreed in the EU context.

It is clear that Greece cannot carry out such a large adjustment all at once, so the partner countries have given Greece many years to bring the debt down and achieve a soft landing for the transition to normal market access and full market interest rates. The Greek government can calculate a long-run path to achieve this adjustment. It can then present and explain this plan to the public (ownership!), motivating as well the underlying growth assumptions and the needed primary fiscal measures to stick to this task. The Covid-19 pandemic and the current high inflation rate will seem like blips in this long-run path.

[1] For comparison, the PDMA just opened a benchmark 10 year bond issue for additional government funding in November 2022. The market bought additional bonds at a cost of 4.44 percent a year.